|

| John Whiteside Parsons |

When residents of north Alabama think of rocket scientists, their thoughts usually turn with pride and nostalgia to Wernher von Braun, the German emigre with the checkered past who made Huntsville his home and whose rockets won the space race by planting Americans, and the Stars and Stripes, on the moon.

Before World War II — long before he came to the U.S. — von Braun corresponded with a young man in California, a man whose place in rocketry is as important if not as widely known.

John Whiteside Parsons was born Marvel Whiteside Parsons in 1914 in Los Angeles. As John Parsons, he co-founded Jet Propulsion Laboratory (now a crucial part of NASA) and Aerojet, which today manufactures strap-on boosters for the Atlas V rockets built by United Launch Alliance in Decatur. Parsons was a pioneer in solid rocket fuel, used to propel small rockets as well as boosters for large rockets and, until recently, the space shuttles. By any measure, Parsons was one of the giants of American rocketry.

He did all this despite his lack of a college degree and formal training. He was, like Emma Peel, a talented amateur, whose enthusiasm, intelligence and daring were more than sufficient for the task. At least until 1952, when his daring got the better of him and he died from wounds he sustained in an explosion in his home laboratory. He was just 37.

That, however, is just half the story, as recounted in two biographies of Parsons: George Pendle's "Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons" and John Carter's "Sex and Rockets: The Occult World of Jack Parsons."

To some, John Whiteside Parsons was better known as Jack Parsons, rocket scientist by day and occultist by night. When he wasn't accidentally blowing up labs on the Caltech campus, he was invoking powers from beyond the sundered veil and corresponding with his friend and mentor Aleister Crowley, the infamous occultist and mystic dubbed the "wickedest man in the world."

Crowley appointed Parsons the head of the American lodge of Crowley's magical order.

But to Crowley's apparent irritation, Parsons was caught up in a third world, the world of science fiction, as an avid reader of the sci-fi magazines that were then in their heyday. It was from the Southern California sci-fi scene, which at the time included the likes of Ray Bradbury and Robert Heinlein, that Parsons met L. Ron Hubbard, pulp writer, charismatic teller of tall tales (mostly about himself) and future founder of Scientology.

From Parsons, Hubbard took two things. First, he picked up some ideas from Parsons' mystical explorations and incorporated them into what would become Scientology. Second, he picked up Parsons' mistress, Betty Northrup. She would go on to marry Hubbard and help him develop his Scientology precursor Dianetics, "the modern science of mental health," before Hubbard denounced her as a communist — at the height of the Red Scare — and the two rather acrimoniously divorced.

And so it came to pass that the man no one called Marvel Parsons became the crossroads of science, science fiction and Scientology during some very formative years for all three.

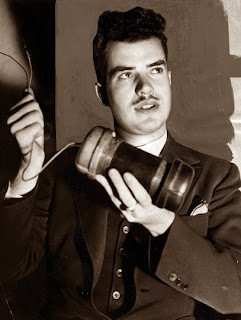

By any standard, Parsons was a character. A handsome young man with a thin mustache, he looked every bit the rakish daredevil. Add to that his status as both rocket scientist and sorcerer, and he was a character writers couldn't pass up. Fictionalized versions of Parsons have appeared in novels and in comics for decades.

Of course this was all too much for respectable rocket science, and Parsons was forced out of the field, retreating to the world of special effects, where he made explosions for the movies, which is probably what he was working on when he made the explosion that killed him.

No comments:

Post a Comment