Thursday, March 28, 2013

Culture Shock 03.28.13: The Day Iraq stood still

What if I told you the justification for the Iraq War was laid out in a 62-year-old science fiction movie?

As unlikely as it may seem, the case for President George W. Bush's preemptive war against the regime of Saddam Hussein is summed up in finale of 1951's "The Day the Earth Stood Still," regarded by many critics — although not this one — as a classic of both sci-fi and Cold War cinema.

Ten years ago, the United States invaded Iraq. That didn't exactly work out as planned, and for the past week, backers of the war, both conservative and liberal, have looked back and wondered, aloud and in print, whether it was worth it.

Some conservative hawks, such as the Weekly Standard's William Kristol, likely will go to their graves defending the Iraq War. But their unrepentant stridency is quite the contrast to the contorted and feckless mea culpas of liberal hawks such as The Washington Post's resident wunderkind Ezra Klein or New York magazine's Jonathan Chait.

In their apologies, Klein and Chait devote the now customary attention to Iraq's phantom weapons of mass destruction and Saddam's supposed mental instability, but neither engages what was the most fundamental issue in the run-up to the war: whether or not preemptive war, in general, is a legitimate course of action. Probably they don't talk about it because, except for what little remains of the Code Pink anti-war left, most liberals and progressives have no problem with preemptive war. It simply isn't a concern.

That attitude certainly comes through in "The Day the Earth Stood Still," which apart from being a movie about aliens, flying saucers and robots, is a liberal message movie.

At the film's conclusion, the alien ambassador Klaatu (Michael Rennie) gives the Earth an ultimatum: "It is no concern of ours how you run your own planet, but if you threaten to extend your violence, this Earth of yours will be reduced to a burned-out cinder. Your choice is simple: Join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration."

Yes, in the 1950s, preemptive genocide when faced with the mere threat of violence from a vastly inferior military force was considered a liberal idea. Go figure. But that was the '50s, and the liberals were the internationalist crusaders (such as Harry Truman, who gave us the Korean War, which still is causing us a spot of trouble today), while the conservatives, such as Republican Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio, were the peaceniks.

Naturally, the movie is more complicated than that. Klaatu is portrayed as an almost Christ-like figure, bringing a promise of hope and peace to the people of Earth, but also the prospect of damnation if we don't mend our ways. And yet the plot point about an army of space-patrolling robots programmed to pounce on any planet that gets too big for its britches remains. And that is kind of hard to ignore. Being the galaxy's policeman versus being the world's policeman is only a difference of degree, not of kind.

Since "The Day the Earth Stood Still" premiered, there has been an ideological shift. In the late '60s and early '70s, some liberals got "mugged by reality" and became neoconservatives. They, their children and those they've influenced are now the face of conservatism. And because they were the most hawkish of liberals, conservatism became more hawkish, too.

So we had a war with a liberal justification, launched by a conservative president, supported by a mix of liberal and conservative pundits and now second-guessed mostly by liberals. And the war became so unpopular it tainted the conservative brand and led to President Barack Obama.

Even when the Earth stands still, politics doesn't.

Thursday, March 21, 2013

Culture Shock 03.21.13: Rocket science has a secret history

|

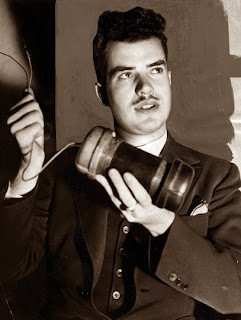

| John Whiteside Parsons |

When residents of north Alabama think of rocket scientists, their thoughts usually turn with pride and nostalgia to Wernher von Braun, the German emigre with the checkered past who made Huntsville his home and whose rockets won the space race by planting Americans, and the Stars and Stripes, on the moon.

Before World War II — long before he came to the U.S. — von Braun corresponded with a young man in California, a man whose place in rocketry is as important if not as widely known.

John Whiteside Parsons was born Marvel Whiteside Parsons in 1914 in Los Angeles. As John Parsons, he co-founded Jet Propulsion Laboratory (now a crucial part of NASA) and Aerojet, which today manufactures strap-on boosters for the Atlas V rockets built by United Launch Alliance in Decatur. Parsons was a pioneer in solid rocket fuel, used to propel small rockets as well as boosters for large rockets and, until recently, the space shuttles. By any measure, Parsons was one of the giants of American rocketry.

He did all this despite his lack of a college degree and formal training. He was, like Emma Peel, a talented amateur, whose enthusiasm, intelligence and daring were more than sufficient for the task. At least until 1952, when his daring got the better of him and he died from wounds he sustained in an explosion in his home laboratory. He was just 37.

That, however, is just half the story, as recounted in two biographies of Parsons: George Pendle's "Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons" and John Carter's "Sex and Rockets: The Occult World of Jack Parsons."

To some, John Whiteside Parsons was better known as Jack Parsons, rocket scientist by day and occultist by night. When he wasn't accidentally blowing up labs on the Caltech campus, he was invoking powers from beyond the sundered veil and corresponding with his friend and mentor Aleister Crowley, the infamous occultist and mystic dubbed the "wickedest man in the world."

Crowley appointed Parsons the head of the American lodge of Crowley's magical order.

But to Crowley's apparent irritation, Parsons was caught up in a third world, the world of science fiction, as an avid reader of the sci-fi magazines that were then in their heyday. It was from the Southern California sci-fi scene, which at the time included the likes of Ray Bradbury and Robert Heinlein, that Parsons met L. Ron Hubbard, pulp writer, charismatic teller of tall tales (mostly about himself) and future founder of Scientology.

From Parsons, Hubbard took two things. First, he picked up some ideas from Parsons' mystical explorations and incorporated them into what would become Scientology. Second, he picked up Parsons' mistress, Betty Northrup. She would go on to marry Hubbard and help him develop his Scientology precursor Dianetics, "the modern science of mental health," before Hubbard denounced her as a communist — at the height of the Red Scare — and the two rather acrimoniously divorced.

And so it came to pass that the man no one called Marvel Parsons became the crossroads of science, science fiction and Scientology during some very formative years for all three.

By any standard, Parsons was a character. A handsome young man with a thin mustache, he looked every bit the rakish daredevil. Add to that his status as both rocket scientist and sorcerer, and he was a character writers couldn't pass up. Fictionalized versions of Parsons have appeared in novels and in comics for decades.

Of course this was all too much for respectable rocket science, and Parsons was forced out of the field, retreating to the world of special effects, where he made explosions for the movies, which is probably what he was working on when he made the explosion that killed him.

Thursday, March 14, 2013

Culture Shock 03.14.13: In search of 'In Search of...'

"This series presents information based in part on theory and conjecture. The producer's purpose is to suggest some possible explanations, but not necessarily the only ones to the mysteries we will examine."

From 1977 to 1982, that was your weekly warning to take the next half hour of television with a heaping spoonful of salt. It was the disclaimer that introduced each episode of "In Search of... ."

Hosted by Leonard Nimoy, "In Search of..." ran for six 24-episode seasons, and by the time it was done, it had become, in a bizarre way, a record of America's fears and obsessions in the years following Vietnam and Watergate. Before "The X-Files" spelled it out for us, here was a show that dealt in alleged conspiracies and cover-ups, while in search of a truth that was certainly "out there."

Now, for the first time, "In Search of..." is available on home video: a mammoth 21-disc DVD box set containing all six seasons of the original series, all eight episodes of the 2002 Sci-Fi Channel revival hosted by Mitch Pileggi of "The X-Files" and the two pilot episodes hosted by Rod Serling.

Before "Ghost Adventures" and "Ghost Hunters," "Ancient Aliens" and "Finding Bigfoot," even before Art Bell first took to the overnight airwaves with "Coast to Coast A.M.," "In Search of..." brought ghosts, UFOs, the Loch Ness Monster and other paranormal phenomena into homes across America. It caught the zeitgeist of the era, when interest in strange phenomena and the boundaries of science, pseudoscience and fantasy seemed to reach a peak, spurred on by the publication in 1968 of Erich von Däniken's best-selling hodgepodge of mythology and UFO lore, "Chariots of the Gods."

Casting Nimoy as host was a stroke of genius. Then as now associated with his role as the sober-minded and logical Mr. Spock, who better was there to get viewers to take seriously notions like "animal ESP" and the lost civilization of Atlantis?

Almost as important was the show's music, by disco producers Laurin Rinder and W. Michael Lewis, which gave the proceedings an appropriately creepy atmosphere. (That's a soundtrack, issued on vinyl in 1977, begging to be re-released.)

If you believe in the paranormal, this DVD set is like Christmas. Yet even if you are a skeptic — as I am — it is a fascinating, if frustrating, look at persistent myths in earlier stages of their evolution. While Mr. Nimoy's fashions are dated, most of the subjects the show investigates are still fodder for basic cable. They still haven't found bigfoot.

But some "In Search of..." topics are one with their time. If you were born after 1980, you probably don't remember when Americans were terrified of killer bees making their way to the U.S. from South America. Nor do you remember when looming climate change wasn't global warming but "The Coming Ice Age." "In Search of..." tackles both, and makes them seem truly terrifying.

Then there's the Bermuda Triangle. Almost no one talks about it anymore, but the area defined by Miami, the island of Bermuda and San Juan, Puerto Rico, was once known for strange goings on and vanished boats and aircraft. Now, with hindsight and better record keeping, we know this heavily traveled area of the Atlantic doesn't even have an unusually high number of disappearances.

Yet unlike most of the paranormal and conspiracy-theory shows now on the air, "In Search of..." can still surprise you. An episode about the disappearance of Amelia Earhart flirts with the outlandish before settling on a more prosaic explanation. And an episode about the Trojan War is actually too skeptical. The latest archaeological evidence indicates the conflict remembered in Homer's epic poem probably did happen, in some form.

In retrospect, "In Search of..." does give us important insights, just not the ones its producers imagined. It's a slice of life from America at its most paranoid and neurotic.

Thursday, March 07, 2013

Culture Shock 03.07.13: Obama's geek cred disappears at warp speed

Election Day has come and gone. The inauguration has passed. Too late, the truth about President Barack Obama has revealed itself.

The president is a fake geek.

Ever since his arms akimbo photo op with the iconic statue of Superman in Metropolis, Ill., the president's adopted home state, Obama has enjoyed an image as the most geek-friendly chief executive in the nation's history. He invited comparisons to the logical Mr. Spock, and his White House responded gamely to a petition asking the administration to build a Death Star. (The White House said no, for once deciding a program was just too expensive.)

The geek community returned the love. Obama appeared in Image Comics' "Savage Dragon" and in a heavily promoted issue of Marvel Comics' "The Amazing Spider-Man."

But with one slip of the tongue, it all vanished faster than Marty McFly's siblings in a snapshot.

During a press conference last week, President Obama said he couldn't force Republican leaders to come to an agreement with him by performing a "Jedi mind meld" on them.

At the speed of Twitter (roughly 0.999 the speed of light), word of the president's fall to the Dark Side spread. He had confused "Star Trek" and its "Vulcan mind meld" with "Star Wars" and its "Jedi mind trick."

What followed was a great disturbance in the Force, as if millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror and wouldn't shut up about it. Within minutes, #ObamaSciFiQuotes was trending: "Beam me up, Chewy," "Set lightsabers to stun," and, combining Obama's faux pas with the news of the day, "These are not the drones you are looking for." Talk about an un-Forced error.

Some fans claim Obama's gaffe wasn't really a gaffe, because in some "Star Wars" spinoff novels, the Jedi are shown performing a "Force meld." I'm not buying this explanation for a second. First, I doubt the president reads "Star Wars" spinoff novels. Second, the novels don't count, and Boba Fett died in the sarlacc pit.

Saying "Jedi mind meld" is like your mom referring to that show you used to watch in reruns when you were a kid as "Star Track." It's a signpost that tells you your next stop is the Clueless Zone, warp factor 9.

So, the president isn't as much of a geek as he let us believe. Perhaps his handlers encouraged the geeky facade to help his image among young people. President Obama isn't the first president to tell a core constituency what it wanted to hear, and his online image certainly benefited from his seeming geekiness.

Yet the more important takeaway is this confirms what has appeared to be true for the past decade: Geeky is the new cool. It's worth faking. Once geeks pretended not to be geeks, but now it's sometimes in the interest of non-geeks to pretend to be geeks.

The idea of fake geeks smashed headlong into gender politics last year when a debate raged online about "fake geek girls." These supposedly are attractive women who pretend to be geeks for nefarious purposes. By early this year, the discussion had made it to mainstream websites like Slate and The Atlantic. A consensus formed that fake geek girls exist only in the insecure minds of male geeks who feel threatened by attractive, geeky women intruding in their He-Man Woman Haters Club.

I've met a lot of attractive female geeks, so I know they're real. But the feminist response about insecure males reeks of its own kind of sexist overgeneralization. There are fake geeks — "poseurs" is a better term — of both sexes. How do I know? Because I've met them, too.

Male or female, don't tell me you're an anime geek if you don't know who Leiji Matsumoto is.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)